Education

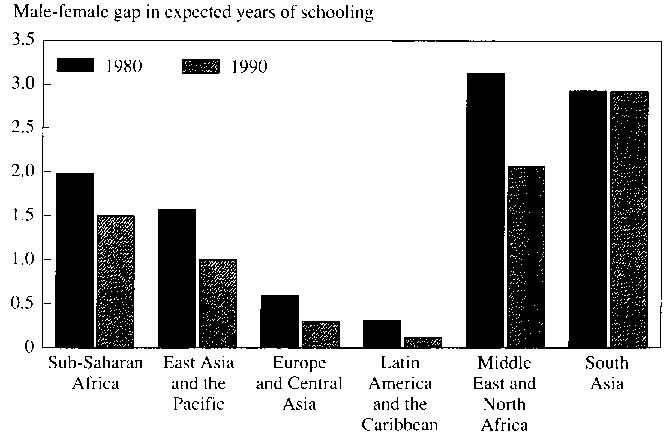

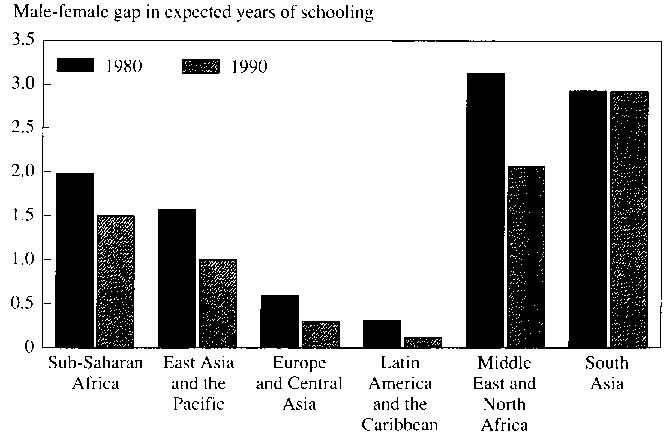

Despite the progress in raising educational enrollment rates for both males and females across all regions in the past three decades, growth in educational opportunities at all levels for females lags behind that for males (figure 1.1). In 1990 an average six-year-old girl in a developing country could expect to attend school for 8.4 years. The figure had increased from 7.3 years in 1980-but an average boy of the same age in a developing country could expect to attend school for 9.7 years The gender gap in expected years of schooling is widest in some countries in South Asia, the Middle East, and Sub-Saharan Africa (see figure 1.2). Gender differences in access to education are usually worse in minority populations such as refugees and internally displaced persons. of which only a few children go to school.

School enrollment ratios in developing countries

The latest available figures show that 77 million girls of primary school age (6-11 years) are not in school, compared with 52 million boys (figure 1.3). Moreover, even these gross enrollment rates often mask high absenteeism and high dropout rates. Dropout rates are notably high in low-income countries but vary by gender worldwide and within regions. The rates for girls tend to be linked to age, peaking at about grade 5 and remaining high at the secondary level (Herz and others 1991) Cultural factors, early marriage, pregnancy, and household responsibilities affect the likelihood that girls will remain in school.

Although the gross enrollment rate is an acceptable indicator of progress in education, most studies use literacy rates as an indicator of well-being. Overall illiteracy rates have decreased among adults in low- and middle-income countries, but the percentage of illiterate women in the world is still higher than the percentage of illiterate men. Older women constitute the largest share of the illiterates in the world today, a consequence of past inequalities in access to education. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia more than 70 percent of women age 25 and older are illiterate (United Nations 1991).

At post-secondary levels. where the gap in enrollment between women and men is wider, there is implicit "gender streaming," or sex segregation, by field of study, even in areas with snore female than male enrollees. Gender streaming. which is widespread in both developing and industrial countries, prevents women from acquiring training in agriculture, forestry, fishing, "hard" sciences, and engineering (figure 1.4).

Expected years of schooling